February de 2020

CURATORSHIP: BLACK EMPOWERMENT THROUGH ART THINKING

Adriana de Oliveira

photos Chuck Martin, Kléber Amâncio, Gismara Oliveira,

Luiz Alves, João Liberato, João Mussolin, MANDELACREW

cover The painter Arthur Timótheo da Costa,

in his studio, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1913.

Amidst the difficulties for penetrating a market that has been for a long time — and still is — almost exclusively white, the curatorship exercised by black men and women represents a path of affirmation, to be conquered and owned.

Fruitful in the formation of utopias, the field of the arts may also amaze by its insistence on maintaining the status quo, especially in a country like Brazil, with a history marked by racism and authoritarianism. It is no coincidence that in the last five years we have witnessed an “emergence” of racially biased art exhibitions, demanding a greater “visibility” of black artists, black issues and black modus operandi.

Among the major black curated exhibitions in recent years in Brazil — both in number of works and institutional visibility — are “Histórias Afro-Atlânticas” (Afro-Atlantic Histories), 2018, at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) and the Tomie Ohtake Institute, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Tomás Toledo, and two black curators Ayrson Heráclito and Hélio Menezes. The exhibition can be understood as a kind of “racialized” continuation, in the topic and curatorial principles, of “Histórias Mestiças” (Mestizo Histories), 2014, curated by Adriano Pedrosa and Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, presented at the Tomie Ohtake Institute; and “Territórios: Artistas Afrodescendentes no Acervo da Pinacoteca” (Territories: Artists of African Descent in the Collection of the Pinacoteca), 2015-2016, at the Estação Pinacoteca, curated by Tadeu Chiarelli. The latter included texts by the black curators Claudinei Roberto da Silva and Fabiana Lopes in their catalog.

Flávio Cerqueira

Amnésia

2015

There were other minor exhibitions organized by black curators, such as ““(Re)conhecendo a Amazônia Negra: Povos, Costumes e Influências Negras na Floresta Negra” ((Re)cognizing the Black Amazon: Black People, their Customs and Influences in the Black Forest) a solo exhibition by the black photographer Marcela Bonfim, curated by photographer Mônica Cardim, at Caixa Cultural (2017); “Agora Somos Todxs Negrxs?” (Are We All Blacks Now?), at the Galpão VideoBrasil (2017), by Daniel de Lima — artist, curator and founding member of the Frente 3 de Fevereiro collective; “Afro como Ascendência, Arte como Procedência” (Afro as Ascendancy, Art as Origin), curated by Alexandre Araújo Bispo, based on the project of the artist and teacher Renata Felinto, at SESC Pinheiros (2013), to name just a few of the ones which occurred in the city of São Paulo downtown area.

BACKGROUND

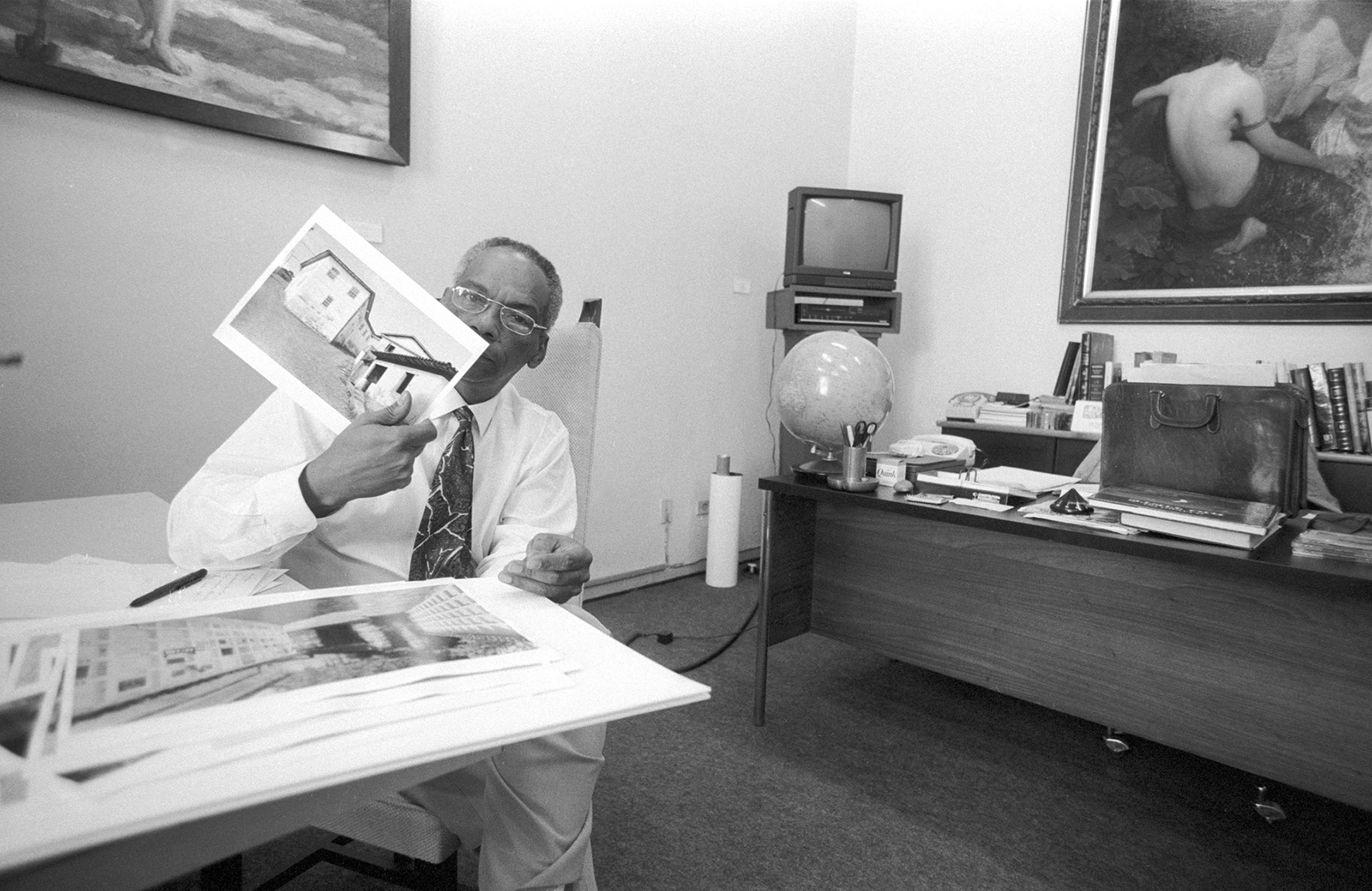

Black curatorial experiences are not recent: just remember the inaugural exhibition of the Museum of Black Art, at Rio de Janeiro’s MIS, ideated by Abdias do Nascimento, in 1968. Or the trajectory of the artist, collector and curator Emanoel Araujo who was the director of Pinacoteca between 1992 and 2002. He purchased works of black artists and organized exhibits such as “Vozes da Diáspora” (Voices of the Diaspora) (1992), and “Herdeiros da Noite: Fragmentos do Imaginário Negro” (Heirs of the Night: Fragments of the Black Imagery) (1995). Emanoel Araujo has also been the curator, at MAM, of the exhibit “A mão Afro-brasileira” (The Afro-Brazilian Hand) (1988), and, as part of the Rediscovery Exhibit, in 2000, of the “Negro de corpo e alma” (Body and Soul Black), a great inventory of the image of black people in Brazil. Araujo, by the way, continues to be the main curatorial reference when it comes to fight racism using art as a sword, a proficiency he gained through exhibits and catalogues, as well as an extensive and collaborative research on the Black question, which culminated in the Afro Brazil Museum, founded by him in 2004. It is also necessary to remember the Brazilian-Congolese anthropologist Kabengele Munanga, who has also acted as curator, with emphasis on the exhibition ““Arte Afro-Brasileira” (Afro-Brazilian Art), which was part of the Discovery Exhibition, in 2000.

Emanoel Araujo in Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 1994

However, one can argue that the pressure for black artists and black curators in Brazil to participate in art became even more decisive when segments of the Brazilian society began to unveil their rejection to black empowerment. This empowerment resulted from popular and governmental actions such as the compulsory inclusion of African and Afro-Brazilian culture in the educational curriculum, the creation of the Secretaria de Políticas de Promoção da Igualdade Racial — SEPPIR (Office of Racial Equality Promotion Policies) in 2003, the promulgation of the Racial Equality Statute in 2010, and the ruling by the Brazilian Supreme Court, in 2012, on the constitutionality of racial quotas.

This broadened context can help to explain why the use of blackface in a play performed at Itaú Cultural Institute in São Paulo, in 2015, sparked numerous protests by black people, resulting in the cancellation of the play. The incident generated a discussion about the representation of black people in arts throughout the country, and about the absence of black artists and curators in important roles in the field of arts. The debate was organized in a series of colloquia titled “Diálogos Ausentes” (Absent Dialogues), curated by Rosana Paulino and Diane Lima, at Itaú Cultural, in 2016.

This kind of uprising by black artists can be considered an indication, in the arts field, in cultural centers, galleries, museums, and other artistic spaces, of a certain openness to the thought and production of black people and other “minority” groups in public spaces and in positions of prestige. It is not a matter of benevolence, as many have indicated, but a strategy for public approaching which does not fail to expressing a market bias. This can be confirmed by the number of visitors attending the ” Histórias Afro-Atlânticas” (Afro-Atlantic Histories) exhibition — 180 thousand at MASP, and 135 thousand at Tomie Ohtake — and the “To the Northeast” exhibition, at SESC 24 de Maio.

On the one hand, it is evident that this is a time of higher recognition for black thinkers in the field of arts, no matter if they are acting as artists, curators, critics, academic or non-academic researchers — if fact, some of them accumulate several of these roles. But, on the other hand, it is worth noting that this same visibility lets out the racism upon which the field of arts, as well as many other in Brazil, are structured.

In this article, we will observe this situation from the point of view of black male and female curators who, with greater frequency and publicity, have been invited or have had projects accepted by cultural institutions of all sizes throughout the country. The professionals presented here emerged from a succinct mapping previously done by O Menelick, but also by those with whom we spoke during our doctoral research on Afro-Brazilian art. These curators named other colleagues, as well.

The majority of the curators mentioned here are from the state of São Paulo or work there, although we were also able to map professionals in Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Pernambuco, Fortaleza, and Rio Grande do Sul. It is a kind of task that, we know in advance, will have absences. Therefore, new additions are more than welcome, as we need to face the “provocation” of Bahian artist and curator Tiago San’Ana, who says: “Do you research, enjoy, and disseminate Afro-Brazilian or Afro-Southeastern art? Because there is a repetition of repertoires in exhibitions, festivals, and publications, despite the diversity of Brazil.”1

EVERYDAY RACISM IN THE ARTS FIELD

At the same time that a greater number of black people have finally taken their positions as proponents of narratives other than mere mestizo or slavery stories, structural and institutional racism has become even more poignant.

Eugenio Lima says, on the challenge of being a black curator or taking any other position involving knowledge production in Brazil: “I have come to understand more and more Carlos Moore’s central thesis that racism is the global system, and capitalism is merely its mode of production.”2 For this actor, DJ, curator, and activist born in Recife and raised in São Paulo, the idea of the Cuban social scientist based in Brazil helps to explain why the ability to narrate and produce knowledge has been denied to non-white people, women, the poor, transsexuals, etc.

However, art is the main battleground to transform this situation, according to Eugenio, because it is the most potent means to create new images and narratives about the black world: “It is not by chance that the term négritude was born in the poetry of Aimé Césaire and then appropriated by politics.”3 And this is why Eugenio Lima defends that black curators, these conveyors of narratives based on art objects, need to be interdisciplinary and inter-sectional. That is, curate music, visual art, scenic art, paintings, sculptures, etc. from a point of view that also takes into account race, gender, and class, just like he has learned from Carla Akotirene and Djamila Ribeiro.

Keyna Eleison

Rio de Janeiro-based professor and curator Keyna Eleison tells that, when she began to work as pedagogical coordinator at the Escola Livre de Arte at Laje Park, in Rio de Janeiro, her body and her ideas made reference to no one less than Lélia Gonzales, anthropologist from Minas Gerais, founder of the Brazilian Unified Black Movement, who had established the Department of Black Studies there.

The perverse detail is that this had happened many years before. “It took the institution forty years to hire another black person for a knowledge producer position. And they only noticed that when I arrived,”4 explains Keyna, stupefied.

Hélio Menezes, Bahian anthropologist based in São Paulo who emerged as a curator at the exhibit ““Histórias Afro-Atlânticas” (Afro-Atlantic Histories), at MASP and at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in 2018, explains that the presence of Black curators on the exhibit’s curatorial team was strategic in order to avoid sharp criticisms like the ones he received for ““Histórias Mestiças” (Mestizo Histories), at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in 2014, and at the seminar that would help to conceptually construct the exhibition in 2014.

“MASP had organized a seminar, ‘Histories of Slavery,’ that was heavily criticized by black artists, researchers, and curators for reaffirming that the history of black populations in Brazil began with slavery, when the research of Black intellectuals demonstrates that this history precedes slavery, and, therefore, the Portuguese domination during the colonial period,”5 he states. Therefore, narrating Afro-Atlantic histories rather than histories of slavery means telling a history from a perspective that is not euro-centric.

“Of course there is an interest in the visuality created by slavery, even because it disrupts the world of art, like in ‘Scipio, the Negro”6, that French artist Paul Cézanne painted inspired by a photograph of a tortured North American enslaved back man. Although the quantity of works that portray slavery, forced labor, torture, and hyper-sexualization of black bodies is massive, it is necessary to go beyond them, if we do not want to reaffirm a history of submission. To do this, according to Hélio Menezes, it was necessary to dive headfirst into the contemporary black production in Brazil and abroad to bring in other visual narratives in which black bodies appear beyond slavery, or, if related to slavery, in a critical way, thus conveying Afro-Atlantic histories that go through slavery, but do not fixate on it.

Another black curator invited to compose the curatorial team of “Histórias Afro-atlânticas” (Afro- Atlantic Histories) was the Bahian Ayrson Heraclito. In the module “Routes and Trances: Africa, Jamaica and Bahia,” part of the exhibition “Afro-Atlantic Histories” Heráclito had the opportunity to display another way of understanding the artistic production arising from the Afro-Atlantic diasporic routes, the subject of his research. He did the same in 2019 at the exhibition “Ounje – Alimento dos Orixás” (Ounje – Food for Orixás), at SESC Ipiranga, in São Paulo, for which he acted as one of the invited curators.

Thinking about the exhibition that Luciara Ribeiro curated, ” Diálogos e Transgressões” (Dialogues and Transgressions), at SESC Santo Amaro, in 2017-2018, the question arises of how to react to those who say that racialized art is not art. The curator says: “For that, it is important to master the (Western) discourse of art, as well as to have a background like mine.”7 (Luciara holds an M.A in Art History from Unifesp and the University of Salamanca, in Spain.) “Many people try to disarm you with arguments art history arguments because they think you do not master the knowledge they do. This is when you show that, apart from knowing what they know, you have a specific knowledge about non-hegemonic artistic productions that they do not have. Then, black researchers, curators, and artists have a bonus, not a deficiency, in relation to their white peers.Hence the fragility of whiteness, which attacks when it realizes it can lose privileges. And we need to be prepared to defend ourselves in a way that surprises white people, instead of attacking for attacking.”8

CURATORSHIP BY FEMALE AND MALE BLACK CURATORS

Most interlocutors conceive curatorship as a process broader than the exhibit itself, which may include the selection, the acquisition of objects, performances and other artistic expressions and their subsequent documentation, analysis and storage, and also the research, planning and assembling of exhibits based on these materials. Far from being just the selection of a set of artistic expressions, curatorship is the construction of points of view. And as such, it can reiterate or de-construct hegemonic reasoning. Some curators emphasize their status as researchers, educators and artists, or even the sum of all these, to affirm (or subvert) their work as curator.

Among those who define themselves most firmly as researchers is Amanda Carneiro. In 2018, she had her first curatorship, the exhibit “Ainda Assim me Levanto” (In Spite of that I Rise), showing the work of Minas Gerais-born artist Sonia Gomes at MASP, where she currently works. That is why she says she’s “acting as curator at the moment,”9 as she’s been working in museums for ten years, but only now is signing a curatorship. Carneiro has worked in the educational sector of the Afro Brazil Museum, as well as a researcher on contemporary African art in Mozambique and Germany. The hesitation to define herself as a curator comes from the fact that she has signed few curatorship so far. And, above all, because she argues that “it is necessary to remove from the curator the sacrosanct role of the guardian of knowledge, contact articulation, and exhibit policies.”10

Research is also the central point for Leandro Muniz: “I am an artist and curator, but I prefer to say I am an artist and researcher,”11 he says. Since he obtained his B.A. in visual arts, he has been working as educator, artist and curatorship assistant, and as curator, independent curator and, more recently, as a reporter for Select, a publication specializing in arts.“I curate because I make art and I am constantly in contact with many artists with whom I want to converse, not only in the private but also in the public sphere, initiating texts, interviews, debates.”12

Igor Simões

In the definition of curatorship by anthropologist, curator and art critic Alexandre Araujo Bispo, the educational and inter-sectional character of the work have a prominent position: “curatorship is selecting and suggesting relationships among things, among points of view. Each work can be considered as at least one point of view. Curatorship is gathering these points of view, these interpretative places, making one think relationships marked by the materiality of objects, and also by the race, gender and social class of their producers, audience and context, all together. And for that, the investment in teams of educators to dialogue with different audiences in the exhibits is quintessential, it is one of the main aspects of a curatorial project.”13

For professor and curator Igor Simões, “Curatorship is a composition, an assembly. Each work is a fragment that articulates with another, either by approximation or detachment. Hence my thinking of objects in ‘state of exhibit’; that is, able to take on different positions in different exhibit arrangements.”14 Igor Simões works at the State University of Rio Grande do Sul (UERGS) and at the Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul (MARGS), where he also interacts with another black curator, Izis Abreu.

Ayrson Heráclito’s simultaneous initiation as ogã, artist and teacher, – in the terreiro, the arts, and the university – marks his experience as curator. “I started curating because I am interested in aesthetic dialogues that test the boundaries between the curator and the artist. So, for me, curating has always been both a contemplative and inventive activity.”15 The experience as ogã — priest in candomblé who is the right hand of the father or mother of Saint of a terreiro, and therefore responsible for the organization of rituals and the security of the incorporated entities – – enables Ayrson to build a long and respectful relationship with the artists he researches and curates.

Another to overlap roles is the Bahian artist and curator Tiago Sant’Ana. By understanding curatorship as “an exercise to recognize artistic projects that are covered up by a perverse aesthetic, poetic, and technical hierarchization,”16 he ends up transforming research that would result in authorial work into a curatorship with various artists. An example of this was the “Kaurís” exhibition at Goethe-Institut in Salvador, in March 2019. The work was based on Salvador’s Revolta de Búzios — one of the most important abolitionist movements in Brazil, but little known. The supporters used cowrie-shells (“búzios” in Portuguese) as a way of identifying themselves, as well as the artists’ works. According to Tiago, the shells make allusion “to freedom and the future through an ancestral reading technique.”17

Claudinei Roberto

One of the most enduring experiences in curating is that of artist, educator and researcher Claudinei Roberto da Silva. At the moment, he is curator of “PretaAtitude” (BlackAttitude), an exhibit that has been traveling the SESC network since 2018. On curatorial choices or styles, their motivations and consequences in the case of black artists and curators, he states: “African- descent artists, we know, face historically determined restrictions that must be reported. Not by chance, the name of the exhibition: ‘PretaAtitude. Emergencies, Insurgencies, Affirmations: Afro-Brazilian Contemporary Art’ (“preta” means black, in Portuguese.) The large amount of works and artists in relation to the space available comes from that, but not only. When we understand the expography of the Afro Brazil Museum, we realize that, by conceiving nuclei with no divisions, that tiresome accumulation of information pops a giant bubble of prejudice. ‘Work and Slavery’ communicate with ‘Sacred and Secular Celebrations,’ which communicate with the ‘Academic Art,’ and with ‘Baroque’. That makes us understand that there is a plural sensitivity with Afro-Atlantic and Afro-Brazilian origins.”18

Museu Afro Brasil, in São Paulo

Claudinei also uses a comparison between MASP and the Afro Brazil Museum to defend his attitude: “It is interesting that MASP’s glass easels are considered revolutionary while the long- term exhibition at the Afro Brazil Museum is considered confusing, because the mental device that triggers one and the other is the same. What do easels do? They allow you to see the last work in perspective with respect to the first, in a space that is not enclosed by walls. And I, as a black curator in a racist country, am not going to claim or reproduce a certain kind of curatorship and expography that has excluded me, or banned me from certain places. Because the white cube, by sanctifying objects, has moved away more than welcomed black subjects and other subordinated subjects in relation to art. I can even do it, because black artists and curators can and should do whatever they want. If they want to do minimalism, abstract or semi-open exhibitions, what is the problem with that? However, what they do, whether they like it or not, they do from their condition of being black. But it is a fact that in ‘PretaAtitude’ I decided to go another way, and present several artists in a rather limited space.”19

BLACK REFERENCES TO APPEASE LONELINESS, SILENCE AND INVISIBILITY

Together with the curator, educator and black photographer Jordana Braz, Luciara Ribeiro idealized the project “Experiências Negras” (Black Experiences), which premiered in August 2019 at the Tomie Ohtake Institute, precisely to promote debates lead by black people who work in various areas at the art and culture institutions of Brazil. Jordana Braz was the only black professional to be part of the team of educators, since the “Afro-Atlantic Histories” exhibition that was housed there, as well as at MASP. Back then, institutional racism became wide open when a banner reading “Where are the blacks?” was posted by the collective 3 of February Front right in the middle of the facade of Tomie Ohtake Institute — a place where blacks were allocated to cleaning, security, and maintenance services. Luciara and Jordana’s first guests were curators Andrea Mendes, Iná Henrique Dias, and Keyna Eleison.

Performer and curator Andrea Mendes conceived the collective Black Embodiments, in Campinas, to support the production of black artists: “Our work always receives a no, people always look with contempt at our art. I’ve been there as an artist. So, as a curator, I have a greater sensitivity. At the same time, I think, ‘gosh, who is going to be my reference as female curator?’ I didn’t know any black curators until then. Fabiana Lopes became my reference, as well as other black curators I met over time. Many times, blacks are not references to each other, but now we are making each other stronger.”20

Iná Henrique Dias is a photojournalist of Jornal Empoderado (Empowered Journal), an independent newspaper focused on “giving voice to the silenced and invisible, the peripherals.” She is also one of the founders of the collective Afrotometry, a word play combining “afro” and “photometry” — the measurement of the intensity of light. A “racialized” collective, as Iná says, to recognize the intensity of the competence of black photographers works. “We did an exhibition at Casa Elefante, in downtown São Paulo, because we found several good black photographers from the poor outskirts of the city, from old school to youngster, such as Vilma Souza, Jéssica Alves, and Júlio César. We have to be everywhere.The joy of participating in an exhibition, of having your work recognized, is a matter of self-esteem.”21 The photographer also revealed her strategy to make up for the lack of material resources: “I started taking pictures in 2012, and my technique was quite poor, I didn’t have very good equipment, so what I did was studying and reading a lot, to know exactly what I wanted, what spot I wanted to claim as mine.”22

In 2019, Keyna Eleison started the Nacional Trovoa in Rio de Janeiro, a collective to bring together “racialized” female artists which rapidly expanded across the country. “Racialized women,” Keyna insists, “because there is a historical, racial cutout in the arts field – the white, male cutout. So, we cannot fall into the trap of separating art and politics; this is the same as saying that art is possible outside the planet, outside humanity.”23

From the selection of black female artists who responded to Trovoa’s invitation, São Paulo-born Carollina Lauriano, sister of artist Jaime Lauriano, proposed the curatorship of the exhibition “A Noite Não Adormecerá Jamais nos Olhos Nossos” (The Night Will Never Fall Asleep in Our Eyes), at the Baró Gallery, in São Paulo, in 2019. Carollina is part of the curatorial team of the Ateliê397, an independent art space in São Paulo. Her central research theme the insertion of women in the art market. We see that the strategy of these black curators is to racialize their experience in the arts world, foster self-esteem by creating a group with equals, and thus break the loneliness, silence and invisibility to which black subjects are often relegated.

BRAZILIAN BLACK CURATORS ACTING LOCALLY AND ABROAD

Acting as independent curator between New York and São Paulo, Fabiana Lopes was the professional most remembered by the curators we interviewed for being a pioneer in claiming a place for the production of black artists in contemporary art spaces.In addition to researching artists and writing about art criticism, Fabiana Lopes does the hard work of asking Brazilian gallery owners about the absence of black artists in the art galleries and, consequently, educating them about the importance and competence of these artists. One of the results was the individual exhibition of artist Lidia Lisbôa, “Entre tramas” (Among woven threads), in the Rabieh Gallery, in the middle of São Paulo’s whiteness territory, the neighborhood of Jardins, in 2015.

Fabiana Lopes

Another curator from São Paulo who alternates between Brazil and abroad is Thiago de Paula Souza. He worked as an educator at the Afro Brasil Museum before taking off with international projects such as the 10th Berlin Biennale, between 2016 and 2018. Invited by South African female curator Gabi Ngcobo, he joined the curatorial team of “We don’t Need Another Hero.” Currently, Thiago is a member of the curatorial team of the third edition of ‘Frestas’ (cracks), the Triennial of Arts at SESC Sorocaba.

Diane Lima also found her place the international scene.In 2019, the creative director and curator from Bahia based in São Paulo worked as co-curator of the “Residência PlusAfrot,” at the “Villa Waldberta,” and of the collective exhibition “Lost Body — Displacement as Choreography,” both in Munich, Germany. In 2018, she was curator of the Valongo International Festival of Image, in Santos, São Paulo. Today, alongside Thiago, she curates the third edition of “Frestas,” the Triennial of Arts at SESC Sorocaba.

MORE CURATORS

In São Paulo, it is also worth mentioning Renato Araújo da Silva who, for over a decade, was a researcher and educator at the Afro Brazil Museum. Among his favorite research topics are African and Afro-Brazilian jewelry, in addition to the very concept of African and Afro-Brazilian art that resulted in curatorial works at the museum. Renato is currently the curator responsible for the research at the Ivani and Jorge Yunes Collection (CIJY), which resulted in the three modules of the exhibition “África” – Mãe de Todos Nós: Conexão entre Mundos, Símbolos de Poder, A Sonoridade da África” (Africa” – Mother of All of Us: Connection Between Worlds, Symbols of Power, The Sound of Africa) on display during the second semester of 2019 at the Oscar Niemeyer Museum, in Curitiba, Paraná.

Still in São Paulo, art historian André Pitol did an extensive research on the Brazilian photographer Alair Gomes, and participated as a curator of the pilot program “Consultas Curatoriais” (Curatorial Consultations), conceived to accompany the production of five residents artists at Pivô, at the Copan Building, in Sao Paulo.

Among curators in Rio de Janeiro it is also worth mentioning the artist and researcher Camilla Rocha Campos, who is currently the artistic director of the artist-in-residence Capacete, a space that has been operating for twenty years; and Rafael Bandeira, at Caixa Preta, an independent space for contemporary art, where they develop collaborative and interdisciplinary experiments and research.

HOW ARE THE BLACK CURATORS DOING?

Undoubtedly, there is greater visibility, but the number of black curators who occupy decision- making positions in cultural institutions is still minimal, since most of them define themselves as “independent curators”. Defining yourself as an independent curator may have a rebellious and charming tone, but it sometimes masks the precarious character in which most of the black curators perform their work.

Curatorship is still a white profession, even when the artistic productions are black.Most of the time, it is still the white curator or white manager who invites or approves the project of the black curator, usually in a sporadic, late, and incomplete way.

Alexandre Bispo

Hélio Menezes says that he and Ayrson Heráclito were called only in the last year of preparing the exhibition “Afro-Atlantic Histories”: “While the white curators, hired by the institution on a permanent basis, had three years of research, we had only one, which meant that we could not choose works from foreign collections, as these institutions plan loans one or one and a half years in advance.”24

Alexandre Bispo also stresses the institutional fragility of black professionals: “We, as black curators, do not yet have an experience of black curatorial abundance in the form of exhibitions, except for Emanoel Araujo. Exhibiting artwork is very expensive, it depends on your relationships and networking in the field, it is not easy. And here in São Paulo, we no longer have Claudinei Roberto da Silva’s Ateliê Oço, which was a simpler and more open structure, focused on non-white Arts. So, as curator, I write more than I set up exhibitions.”25

In order to curate the exhibition “Em Três Tempos: Memória, Viagem e Água” (In Three Times: Memory, Travel and water), by Aline Motta, at the Cultural Center of TCU, in Brasilia, in August 2019, Bispo had to research the black and mestizo family in Brazil. In doing so, he imagined an exhibition that would bring together works by Albert Eckhout, Tarsila do Amaral, Lasar Segall, Guignard, Eustáquio Neves, Rosana Paulino, and Renata Felinto, among other artists whose works bring out multiple views of the black and mestizo family in Brazil.

Alexandre also points out that the black curator is often invited to participate only at the end of the curatorial process. Although he is responsible for the selection and the dialogue with the artists, in terms of the exhibit, his role is usually writing the curatorial text, but not taking the decisions regarding the assembly of the exhibition, usually carried out by the institution that invites him.

Despite the countless difficulties, one thing is granted: black artists and curators will not stop claiming their physical and intellectual presence in spaces of white privilege.The hiring of black people for management or curatorial positions is encouraging. In this sense, Renata Bittencourt has just taken up the post of executive director of the Inhotim Institute in Brumadinho, and due to her academic and institutional trajectory, we hope that this new position of power will benefit women, black, native and trans artists.

We have seen that exhibitions with black curators are an emergency, in the sense proposed by the editors of O Menelick when they thought of this issue, that is, something at one time ascending and urgent. An uprising, therefore, just like the closed fist black power, ready to deconstruct a scenario described by most of the curators in this article as “hegemonic”, “colonized”, “Eurocentric”, “homophobic”, “misogynist” etc. In short, “white”.

Mere fashion or a real decolonization of the way of producing, thinking and displaying the various black expressions in Brazil? In order to build “a territory of Afro-Brazilian art”, according to Rosana Paulino, it is necessary to set up a tripod, which consists of fostering research, the production, and the circulation of art produced by black artists. “Fostering production is ensuring conditions for artists to produce a lot and freely. For this, it is important to research, to criticize, and to document in film and in photographs. These feedback circulation, which is both the exhibition and the acquisition of works by collectors and public and private institutions. This has been Claudinei Roberto da Silva’s work for a long time and now, more regularly, in SESC network, where he has been proposing exhibitions that make works circulate and be sold. And we have to write too, otherwise someone will write for us,”26 he points out.

TREMBLING CURATORSHIP

Ana Lira prefers not to define herself as a curator, since she sees herself as “an artist who articulates processes, including curatorial processes”. As an indication of this, she sent us a message about the opening, in August 2019, of the “36a. Panorama da Arte Brasileira – Sertão” (36th. Brazilian Art Overview — Hinterland), at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MAM), where she featured photographs of the work of male and female farmers she followed in the northeastern semiarid. It should be noted that, by choosing the “sertão” and “non-hegemonic creation strategies and new social technologies”, MAM is another great cultural institution that has rehearsed a more northeastern direction.

Luciara Ribeiro also hesitates to consider herself as a curator: “I see myself more as a researcher. If curatorship means a hierarchical place, I don’t want to take on this label. On the contrary, we need to think about more collaborative strategies.”

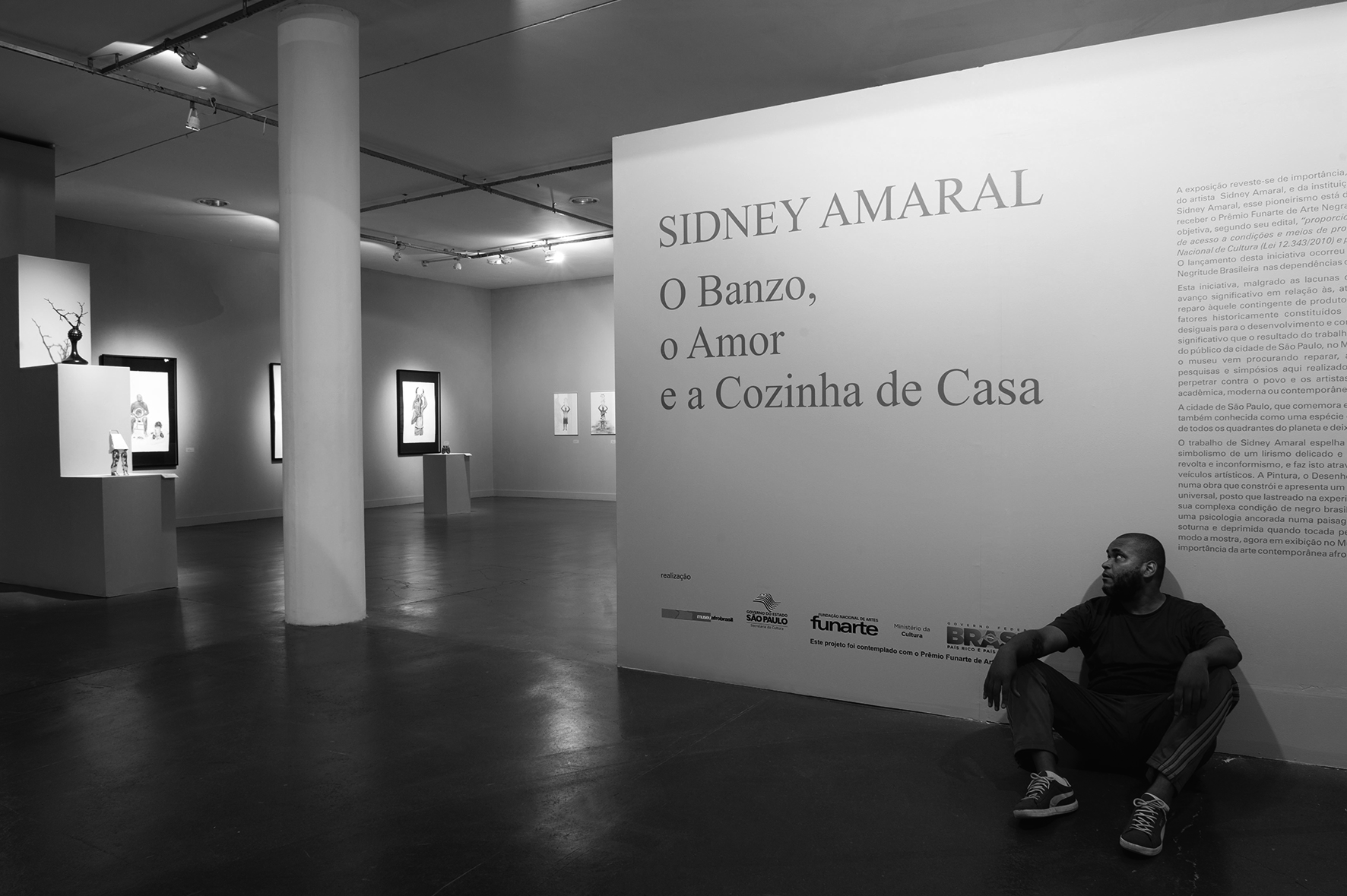

The artist Sidney Amaral in his first solo exhibition. Museu Afro Brasil, São Paulo, 2014

After a number of exhibitions, artist, educator, and curator Durval Roberto da Silva said he only presented himself as curator with two exhibits in 2015. The first one, “O amor: modos e usos” (Love: modes and uses), by Rosana Paulino, he organized in 2011, at Ateliê Oço, a space designed and maintained by him from 2009 to 2015. The second was Sidney Amaral’s “O Banzo, o Amor e a Cozinha de Casa” (Banzo, Love and our Home Kitchen) at the Afro Brazil Museum.

The number of curators who hesitate to assume this position is striking. Undoubtedly, the argument of not wanting to assume an authoritarian and centralizing and hierarchical role, reproducing a modus operandi often qualified as “hegemonic” and “white”, is defensible. However, it can also conceal a refusal to take power, as powerful black women and men are not the rule in Brazil. Keyna Eleison was the one who drew attention to this difficulty in calling herself a curator, due to structural racism, even more marked in the field of arts. “It took me a long time to come out as a curator. ‘Curator, me?’ I used to tremble to think of myself as a curator. And why, if I had much more experience and work done as a curator than many white colleagues? Because everything around me was still telling me this is not a common position for blacks. Having the power to think, to build narratives is supposedly a white people thing. Despite all my formal education, all my erudition, I still felt trembling.”

SOUTHEASTWARD

On the assumption that São Paulo would outshine artistic and curatorial opportunities in other cities and states in Brazil, Hélio Menezes says that it is not an internal problem to black female and male curators. According to the Bahian curator, “It’s really more a discussion about how the cultural institutions in São Paulo concentrate income, power and, as a result, a large number of exhibitions, publications, and universities. So, it’s not a deliberate action to delete other artistic expressions from outside of São Paulo.” “Interestingly, São Paulo brings together, on the one hand, a large number of curators and inheriting artists, usually white, who — of course — do not depend on their craft to stay alive. And we, black subjects, who often leave our land to come here live on art, because this is where money flows. This is what happened to me and to so many other curators and artists who come here, or who remained in their states, but in constant dialogue with São Paulo, such as Ayrson Heráclito, Diane Lima, Bitu Cassundé, among many others.”

NORTHEASTWARD

The exhibition “A Nordeste” (Northeastward), on show at SESC 24 de Maio, in São Paulo, shows clearly what its black curators think about curatorship. Bitu Cassundé, curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ceará and coordinator of the Laboratory of Visual Arts of Porto Iracema, in the city of Fortaleza; Marcelo Campos, curator at the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Art; and curator Clarissa Diniz also is made explicit their response to the criticism of Aracy Amaral on the exhibition. More than asking themselves what curatorship is, they have asked: “curatorship for what, and for whom?” And their response was: “To expose other trajectories, other intentions, other desires, other protagonists, other emergencies, other artists, other northeast.”

Bitu Cassundé

Curatorship is not an easy task. From the fragments of experiences compiled here, we have seen how the cumulative, the exaggeration, the violence, the un-digestible, the crowd, the labyrinth, the whirlwind, the choice of not prioritizing a point of view over the other, the decision of not dying, in short, ties a knot in the whiteness heads. But what other ways we have to build, narrate, and competently expose the experience of women, native, black, trans and other non- white people in a racist, fascist, and authoritarian country like Brazil? May there be more curatorship with this power ‘northeastward,’ reaffirming with impertinence the pertinence of non- hegemonic experiences in art.