February de 2020

READING FRANTZ FANON IN THE ERA OF BLACK LIVES MATTER

Frieda Ekotto.

fotos Adam Wold

“What matters is not to know the world but to change it”.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks

Today, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, after Barack Obama’s presidency and in the era of Donald Trump, after the violent events of Ferguson, Missouri and Staten Island, New York, and as we watch the rise of white nationalism in Charlottesville, Virginia, Christchurch, New Zealand, and recent mass shooting in El Paso, Texas and Dayton, Ohio to name just a few places, racial politics remain entrenched in American life. In addition, as the refugee crises, the potential withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, and the 2019 parliamentary elections in Europe have shown, reverberations of the colonial past are palpable in contemporary upheaval, discord, and violence. These societal ills all have their origins in history and memory, origins that have often been overlooked, if not erased, even as they continue to affect our contemporary world.

To address this history alongside current events, this paper reads Black Lives Matter together with Frantz Fanon’s work on the struggle for the dignity of Black people around the world. It demonstrates how, in addition to the work of Négritude thinkers (Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Léon Damas, and W.E.B. Du Bois), Fanon’s writing offers the historical background necessary for understanding the Black Lives Matter movement and, more broadly, the Black American experience during the second decade of the twenty-first century. Fanon was among the first to articulate enduring questions about the Black condition in the world, and his theoretical insights establish why there will be no peace as long as the dignity of Black men, women, and children are ignored, their lives crushed.

W.E.B Du Bois, Boston (1907)

Fanon’s seminal articulation of how colonialism produces trauma, chaos, and loss only grows in importance as time passes. In his work, he confronts the disturbing ways in which racial violence is repeated due to its entrenchment in the cultural imaginary, and despite Black subjects’ efforts to speak out against domination. In this chapter, I will focus upon how his work can help us to better understand the Black Lives Matter movement, which has undertaken the recuperative work of exposing violence against Black people by bringing attention to whiteness and the White gaze. I give particular attention to Fanon’s insights into the violence of the Black condition and how Black people must transform this violence into acts of resistance. I begin by discussing a formative moment in Fanon’s text Black Skin/White Masks, when he first felt consciously compelled to transfrom the violence of the White gaze into action. I then describe how the Black Lives Matter movement has channeled quotidian violence against Black Americans into a powerful movement. I finish by reflecting upon the continuity between Black Lives Matter and previous American movements, even as I consider how its unique qualities appear to be shaping new modes of representation in mainstream media.

As a young man, Fanon embraced Jean-Paul Sartre’s concept of “committed literature,”[i] and, at the age of 26, he wrote Black Skin, White Masks (1952) with a clear purpose: to identify racism, its societal underpinnings and functioning, its effects on Black men such as himself, and, most importantly, the necessity of action in the face of discrimination. Fanon, in his work as a psychoanalytic theorist, he powerfully evoked the ongoing traumas of racism and the therapeutics of psychic and social change.

Fanon foregrounds the moment he saught to transform this violence against Black men into action in the opening lines of “The Fact of Blackness,” a critical chapter in Black Skin, White Masks. There he recounts two overwhelming and emblematic verbal attacks on his personhood, which he endures as a Black man living in France. They are, first, the common epitath “Dirty nigger!” and, second, “simply,” as Fanon puts it, a young boy’s casual remark to his mother, “Look, a Negro!” (Fanon p. 109).[ii] These remarks, by being both extraordinary and quotidian, bring Fanon to reflect upon the paradox of living as a Black man in a rascist, colonial society.

“I came into the world imbued with the will to find a meaning in things, my spirit filled with desire to attain to the source of the world, and then I found that I was an object in the midst of other objects”. (Fanon p. 109)

Raw and paralyzed by objectification, Fanon finds himself being restored to the world by the attention of others—the very liberating and vital attention of witnessing—only, and almost immediately, to “[fumble] … the movements, the attitudes, the glances of the other [fixing] me there…” (Fanon 1967, p. 109). He thus begins to present the paradox that is a key element in his work: the fact of being both seen and not-seen. One generally feels that in being seen one is given value, and thus one seeks it out, but what Fanon realizes is that, as a Black man, he is fundamentally not being seen; he is only present as an object. This moment is of pivital importance; however, because the realization it provokes compels to Fanon to take action to transform a White imaginary that insists on the objectification of Black men. He also claims with much controversy that blackness—as most Blacks live and experience it—is actually a creation of, and a reaction to, whiteness, white history and culture, as well as white racial and colonial imaginaries.

In exposing the fact that most Black lived experiences have been and remain constructed (or deliberately destructed) by Whites, Fanon seeks not to devalue the Black experience but to foster an anti-racist and, ultimately, revoluvionary-humanist, active critical consciousness among Blacks (as well as among other non-Whites and Whites). This active consciousness is what makes Fanon’s work key to contemporary anti-racism movements such as Black Lives Matter. His call resonates, for example with that of Alicia Garza, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement. In October 2014, she issued the following “herstory”:

“Black Lives Matter is about: how do we live in a world that dehumanizes us and still be human? The fight is not just being able to keep breathing as a human. The fight is actually to be able to walk down the street with your head held high—and feel like I belong here, or I deserve to be here, or I just have a right to have a level of dignity”. (n.p.)

In her articulation of a right to live in the world with dignity, Garza directly engages Fanon’s experience with the young boy, who so casually remarks on Fanon’s blackness. For Garza, this fight for dignity is urgent. In contemporary America, boys can carry guns and casual racism can too frequently turn fatal. It is for this reason that Black Lives Matter demands that Americans draw their attention to the relationship between casual, unexamined rascism, the frequent deaths of Black men, and the equally frequent aquitals of White perpetrators. Since George Zimmerman, a white vigilante, was aquitted of killing Trayvon Martin in 2012, Black Lives Matter has insisted that American face the fact of brutality against young Black men. Even more, it has asked for action to holistically recognize the reasons for and the results of systemic, racialised violence.

In the United States, reoccurring violence is incurred, in part, because of persistent clichés about young Black men, which continue to feed the imagination of some police officers as well as the public. This appears, starkly, in the words of Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. In an interview that appeared in The New Yorker a year after the shooting, Wilson is quoted as saying: “We can’t fix in thirty minutes what happened thirty years ago … We have to fix what’s happening now. That’s my job as a police officer. I’m not going to delve into people’s life-long history and figure out why they’re feeling a certain way, in a certain moment” (quoted in Halpern 2015). Here Wilson suggests that racial violence has nothing to do with him. Rather he identifies the problem to be with “people’s life-long history.” In so doing, he indicates that even a year after the event, when he could have had the opportunity to reflect upon his actions, he still maintains that America’s racialized history is not his own, and that other people (Black people) need to figure out how they feel, or, rather, how not to feel the effects of a racist police state upon their daily lives. Then he can go about his job.

Frantz Fanon // illustration by @edson.ike

As Wilson’s case so starkly demonstrates, this denial of the importance of history and the refusal to examine one’s own perception continue to inflict violence upon citizens in the United States (and around the globe). It also brings us back to Fanon, who insisted that we do feel, and even more than we act. The “universe” into which Blacks find themselves is anti-Black, racist, and white supremacist. It is not a world that Black individuals have created or constructed. Thus, Fanon argues that we “must be extricated” from this inhospitable universe because Black individuals are not and cannot truly live, in any sense of the word, free, proud, and productive human lives in this current world.

Wilson’s suggestion that he is not implicated in conditions of blackness is not a new one. Over at least the past one hundred years, Black writers, thinkers, and artists have documented similar refusals to confront this reality.[iii] Yet it remains invisible because its perpetuation is controlled by dominant discourses. (Wilson’s comments make this point clearly enough.) One of the innovations of the Black Lives Matter movement is its use of social media to shift the focus of the gaze from Black bodies to the violence itself. This, in itself, is not new. We find the same idea, for example, in the words of Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Black Orpheus.” Writing from the perspective of a Black man, he challenges his readers “ to feel, as I, the sensation of being seen. For the White man has enjoyed for three thousand years the privilege of seeing without being seen” (Sartre 1948, p. 7). He continues: “Today, these Black men have fixed their gaze upon us and our gaze is thrown back in our eyes” (Sartre 1948, pp. 7–8). Yet the Black Lives Matter movement returns the White gaze with an important difference. It uses social media as a platform to demand that Black people be treated as human beings. This, in fact is an important intervention into the history of the White gaze. Today, anyone can snap a picture that has the potential to circulate globally. As accesibility and ubiquity have made images of violence commonplace, Black Lives Matter has created a model for how to use technology to continue the fight for Black dignity.

Drawing from this important contemporary intervention, Black scholars are increasingly vocal in their insistance that White individuals examine both their own behaviors as well as their adherance to abstract ideas of nation, country and justice. As with Fanon, they are asking for a holistic examination of how institutions perpetuate and even enforce racial injustice that affects the well-being—and indeed the very lives—of Black Americans. In his opionion article for the New York Times, “Sacrificing Black Lives for the American Lie,” Ibrahim X. Kendi compellingly responds to a Minnesota jury’s decision, which places the responsibility for Philando Castile’s death, not on the police officer who shot him, but on Castille himself—despite video evidence to the contrary. Kendi argues:

“This blaming of the Black victim stands in the way of change that might prevent more victims of violent policing in the future. Could it be that some Americans would rather Black people die than their perceptions of America? Is Black death more palatable than accepting the racist reality of slaveholding America, of segregating America, of mass-incarcerating America? Is Black death the cost of maintaining the myth of a just and meritorious America?” (Kendi 2017)

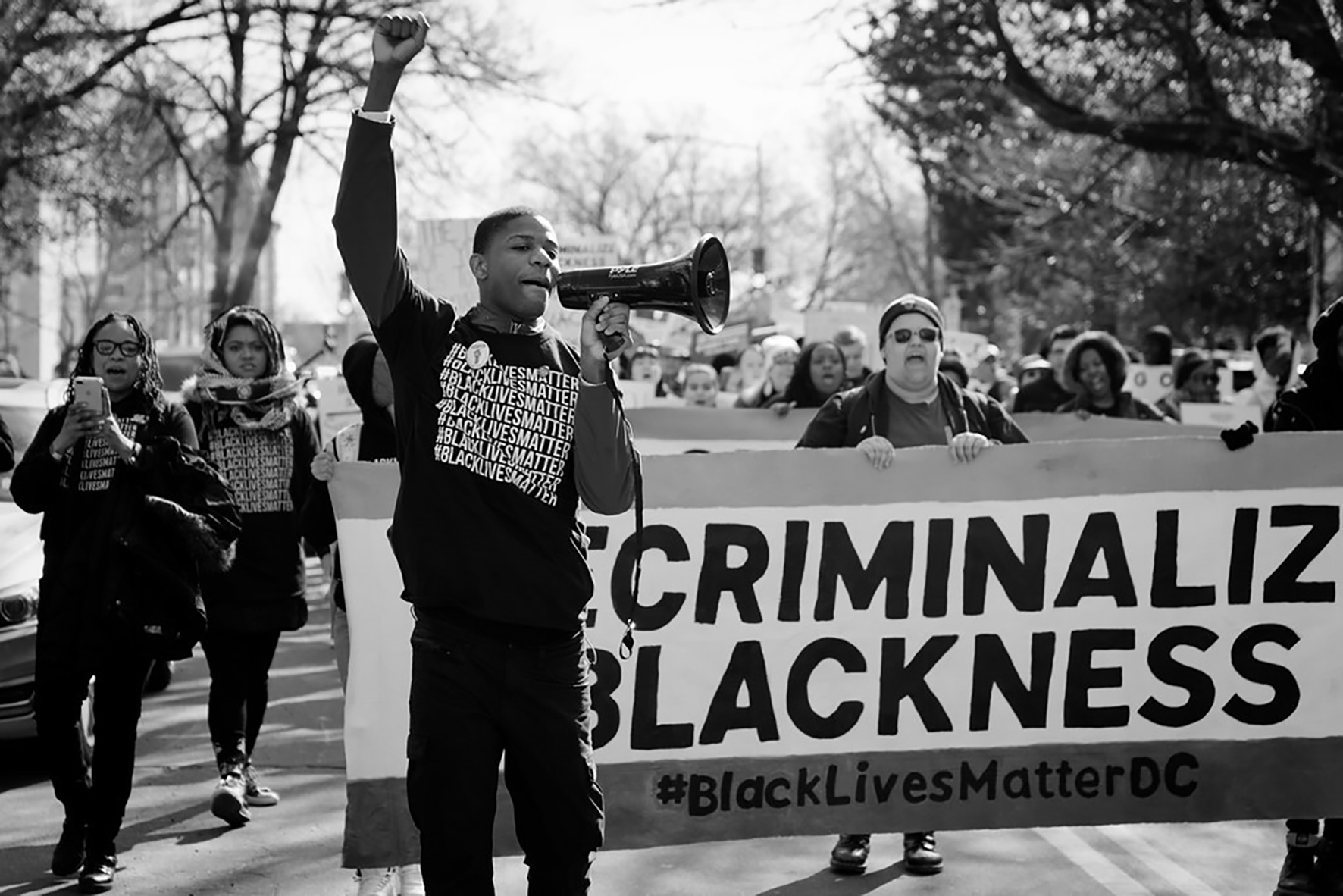

Black Lives Matter DC

Kendi’s call echoes Fanon’s: to make claim to the validity of perspectives that come from the very experience of suffering, and the importance of fighting against forces that have created, perpetuated and hidden the depths of this systemic racism.

Black Lives Matter continues the struggle for dignity, which Fanon and other thinkers demanded in the early twentieth century. Yet, while Fanon’s work is rooted in the complex history of blackness and anticolonial struggle, Black Lives Matter engages with similar conditions with the current situation of police brutality. But there is one issue, for which I find the leaders of Black Lives Matter move beyond Fanon’s own limitations: By bringing their own diversity of background and experience, they have expanded the range of people for whom it is essential to fight.[iv]

Garza and the movement’s co-founders, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi, are not only feminists and members of BOLD (Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity); they are also active and vocal in their fight for LGBTQ rights. Garza, for example, has openly confronted the fact that, although their movement has been created by feminists and lesbians (Patrisse Cullors is openly gay), patriarchy—Black as well as White—continues to usurp their voices. Garza writes:

“Straight men, unintentionally or intentionally, have taken the work of queer Black women and erased our contributions. Perhaps if we were the charismatic Black men many are rallying around these days, it would have been a different story, but being Black queer women in this society (and apparently within these movements) tends to equal invisibility and non-relevancy”. (n.p.)

Black Lives Matter, Minneapolis (2015)

That is why, for Garza, Black rights must converge with the rights of other groups, particularly gay, trans, and disabled people who are oppressed in their own Black communities. Each of these groups has had significant and unique experiences, and they often draw from these experiences in their calls to action. Indeed, Black Lives Matter goes beyond divisions that can be found within some Black communities, which call on Black people to love Black, live Black and buy Black, and which keep straight Black men in the front of the movement, while sisters, people who identify as queer and trans, and disabled folk are given background role or not acknowledged at all. Black Lives Matter affirms the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, the undocumented, individuals with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum.

The coexistence between Black and gay rights is an important part of American history. It is one of the greatest alliances, a true legacy. It is crucial to interrogate the impact of the exclusions that accompanies acts of categorization and engage with the experiences of marginalized subjects in their multiple facets in order demonstrate the dysfunction of categories. Black Lives Movement does not display Black men walking next to those whom they victimize merely to create divisions. They do this to acknowledge that racism, sexism and homophobia together continue racist and colonial iterations of otherness.

In the end, the fact of blackness remains the bedrock of historical reality for Black people around the world, even as the communication of this trauma entails a psychosocial compromise formation that necessitates a careful titration of these truths. I would contend, in accordance with Audre Lorde, that “it is not difference which immobilizes us but silence” (Lorde 1984, p. 144). Given that sexism, racism, and homophobia are “real conditions of all of our lives in this place and time,” our responsibility for the oppression of others (even as we are oppressed ourselves) requires that we “reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside [ourselves] and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there” in order that we “[s]ee whose face it wears” (Lorde 1984, p. 113).

Black Lives Matter, Minneapolis (2015)

“In the work of survival, we must break silences and respond to others, to make what Lorde calls poetry: the “revelatory distillation of experience” (Lorde 1984, p. 37). It is here that we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival, heal the devastating rifts between subjects produced and multiplied by trauma, and address oppressive and hierarchical constructions of difference in the psychosocial spaces (and there are no other) where communication and communion take place”. (Lorde 1984, p. 37).

This work is continuing, and even gathering momentum in such mainstream forums as Netflix, which in summer 2019 released the series When They See Us, about the infamous, false convictions of five men of color, Kharey Wise, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam and Raymond Santana Jr. on charges of a violent assault and rape, which occurred in New York’s Central Park in the spring of 1989. The expressed purpose of this series is to expose the way racial perceptions continue to allow these kinds of gross injustices to occur. In an inteview, director, co-writer and executive producer Ava DuVernay describes why she wanted the series to be called When They See Us rather than “Central Park Five,” which had been the series’ working title. She explains, “‘Central Park Five’ felt like something that had been put upon the real men by the press, the prosecutors, by the police. It took away their faces; it took away their families; it took away their pulses and their beating hearts. It dehumanized them. They are Yusef, Antron, Kevin, Raymond and Kharey, and we need to know them and say their names.” This act of revising history and making claims to names is just another way that contemporary Black activists are forcing discussions of whiteness into contemporary American discourse. They are inisting that Americans reassess their assumptions about how Black people are seen in contemporary American society. When They See Us recounts the complex racial circumstances that brough these boys to prison for the crime of being Black or Latino. It, along with other Black activists, asks us to consider the loss of dignity, of freedom, even of life, that, as Claudia Rankine writes in her book Citizen: An American Lyric, continues to be inscribed upon Black bodies and Black skin. Until this memory, this history and this present moment are seen, acknowledged, and honored, until White police officers can no longer offhandedly remark, “Look, a Black man,” and proceed to arrest or shoot him, the violence inflicted upon Black bodies will continue, and the dignity due to Blacks will be denied.

notes

[i] Littérature engagée, articulated by Sartre in “Qu’est-ce que la littérature.” For Sartre, to write was to take action.

[ii] The original expressions read “Sale nègre” and “Tiens, un nègre.”

[iii] The Congolese philosopher Valentin Yves Mudimbe beautifully articulated that memory is part of history in The Idea of Africa. See Mudimbe 1994.

[iv] We find in contempary readings discomfort with Fanon’s apparent disregard for women. This is perhaps most clearly manifested by the fact that he never directly cites his engagement with the work of Simone de Beauvoir, which is was certainly important to the development of his ideas. As displayed in the film Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin White Mask by Isaac Julien (1995), Fanon was also homophobic.